The New First Grade: Too Much Too Soon?

Kids as young as 6 are tested, and tested again, to ensure they're making sufficient progress. Then there's homework, more workbooks and tutoring.

By Peg Tyre

Newsweek

Sept. 11, 2006 issue -

Brian And Tiffany Aske of Oakland, Calif., desperately want their daughter, Ashlyn, to succeed in first grade. That's why they're moving—to Washington State. When they started Ashlyn in kindergarten last year, they had no reason to worry. A bright child with twinkling eyes, Ashlyn was eager to learn, and the neighborhood school had a great reputation. But by November, Ashlyn, then 5, wasn't measuring up. No matter how many times she was tested, she couldn't read the 130-word list her teacher gave her: words like "our," "house" and "there." She became so exhausted and distraught over homework—including a weekly essay on "my favorite animal" or "my family vacation"—that she would put her head down on the dining-room table and sob. "She would tell me, 'I can't write a story, Mama. I just can't do it'," recalls Tiffany, a stay-at-home mom.

The teacher didn't seem to notice that Ashlyn was crumbling, but Tiffany became so concerned that she began to spend time in her daughter's classroom as a volunteer. There she was both disturbed and comforted to see that other kids were struggling, too. "I saw kids falling asleep at their desks at 11 a.m.," she says. At the end of the year, Tiffany asked the teacher what Ashlyn could expect when she moved on to the first grade. The requirements the teacher described, more words and more math at an even faster pace, "were overwhelming. It was just bizarre."

So Tiffany and Brian, a contractor, looked hard at their family finances to see if they could afford to send Ashlyn to private school. Eventually, they called a real-estate agent in a community where school was not as intense.

In the last decade, the earliest years of schooling have become less like a trip to "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" and more like SAT prep. Thirty years ago first grade was for learning how to read. Now, reading lessons start in kindergarten and kids who don't crack the code by the middle of the first grade get extra help. Instead of story time, finger painting, tracing letters and snack, first graders are spending hours doing math work sheets and sounding out words in reading groups. In some places, recess, music, art and even social studies are being replaced by writing exercises and spelling quizzes. Kids as young as 6 are tested, and tested again—some every 10 days or so—to ensure they're making sufficient progress. After school, there's homework, and for some, educational videos, more workbooks and tutoring, to help give them an edge.

Not every school, or every district, embraces this new work ethic, and in those that do, many kids are thriving. But some children are getting their first taste of failure before they learn to tie their shoes. Being held back a grade was once relatively rare: it makes kids feel singled out and, in some cases, humiliated. These days, the number of kids repeating a grade, especially in urban school districts, has jumped. In Buffalo, N.Y., the district sent a group of more than 600 low-performing first graders to mandatory summer school; even so, 42 percent of them have to repeat the grade. Among affluent families, the pressure to succeed at younger and younger ages is an inevitable byproduct of an increasingly competitive world. The same parents who played Mozart to their kids in utero are willing to spend big bucks to make sure their 5-year-olds don't stray off course.

Like many of his friends, Robert Cloud, a president of an engineering company in suburban Chicago, had the Ivy League in mind when he enrolled his sons, ages 5 and 8, in a weekly after-school tutoring program. "To get into a good school, you need to have good grades," he says. In Granville, Ohio, a city known for its overachieving high-school and middle-school students, an elementary-school principal has noticed a dramatic shift over the past 10 years. "Kindergarten, which was once very play-based," says William White, "has become the new first grade." This pendulum has been swinging for nearly a century: in some decades, educators have favored a rigid academic curriculum, in others, a more child-friendly classroom style. Lately, some experts have begun to question whether our current emphasis on early learning may be going too far.

"There comes a time when prudent people begin to wonder just how high we can raise our expectations for our littlest schoolkids," says Walter Gilliam, a child-development expert at Yale University. Early education, he says, is not just about teaching letters but about turning curious kids into lifelong learners. It's critical that all kids know how to read, but that is only one aspect of a child's education. Are we pushing our children too far, too fast? Could all this pressure be bad for our kids?

Kindergarten and first grade have changed so much because we know so much more about how kids learn. Forty years ago school performance and intelligence were thought to be determined mainly by social conditions—poor kids came from chaotic families and attended badly run schools. If poor children, blacks and Hispanics lagged behind middle-class kids in school, policymakers dismissed the problem as an inevitable byproduct of poverty. Its roots were too deep and complex, and there wasn't the political will to fix it anyway. Since then, scientists have confirmed what some kindergarten teachers had been saying all along—that all young children are wired to learn from birth and an enriched environment, one with plenty of books, stories, rhyming and conversation, can help kids from all kinds of backgrounds achieve more.

Politicians began taking aim at the achievement gap, pushing schools to reconceive the early years as an opportunity to make sure that all kids got the fundamentals of reading and math. At the same time, politicians began calling for tests that would measure how individual students were doing, and high-stakes testing quickly became the sole metric by which a school was measured.

President George W. Bush's No Child Left Behind Act, which required every principal in the country to make sure the kids in his or her school could read by the third grade, was signed into federal law in 2002. Its aim was both simple and breathtakingly grand: to level the academic playing field by holding schools accountable or risk being shut down.

So if the curriculum at Coronita Elementary School, 60 miles outside Los Angeles, is intense, that's because it has to be. Seventy percent of kids who go there live below the poverty line.

Thirty percent don't speak English at home. Even so, No Child Left Behind mandates that Coronita principal Alma Backer and her staff get every student reading proficiently in time for the California state test in the spring of second grade or face stiff penalties: the school could lose its funding and the principal could lose her job. "Our challenges are great," she says. "From day one, our kids are playing catch-up."

First grade is like literacy boot camp. Music, dance, art, phys ed—even social studies and science—take a back seat to reading and writing. Kids are tested every eight weeks to see if they are hitting school, district and statewide benchmarks. If they aren't, they get remedial help, one-on-one tutoring and more instruction. The regular school day starts at 7:45 a.m. and ends at 2:05 p.m.; about a fifth of the students go to an after-school program until 5:30, where they get even more instruction: tutoring, reading group and homework help. Backer says most parents appreciate what the school is trying to do. "Many of them have a high-school diploma or less," says Backer, "but they're still ambitious for their children."

Parents whose kids attend Clemmons Elementary School near Winston-Salem, N.C., are ambitious for their children, too. But the scale of their expectations is different: the upper-middle-class, college-educated parents in this district don't just want their kids to get a good education, they want them to be academic stars. Principal Ron Montaquila says kids of all ages are affected. Last year, says Montaquila, one dad wanted to know how his son stacked up against his classmates. "I told him we didn't do class ranking in kindergarten," recalls Montaquila. But the father persisted. If they did do rankings, the dad asked, would the boy be in the top 10th?

Like almost all elementary schools, kindergarten and first grade at Clemmons have become more academic—but not because of No Child Left Behind. Unlike poor schools, wealthy schools do not depend on federal money. The kids come to school knowing more than they used to. "Many of our kindergartners come in with four years of preschool on their résumé," says Montaquila. Last year nine children started kindergarten at Clemmons reading chapter books—including one who had already tackled "Little House on the Prairie."

In wealthier communities, where parents can afford an extra year of day care or preschool, they are holding their kids out of kindergarten a year—a practice known in sports circles as red-shirting—so their kids can get a jump on the competition. Clemmons parent Mary DeLucia did it.

When her son, Austin, was 5, he was mature, capable, social and ready for school. But the word around the local Starbucks was that kindergarten was a killer. "Other parents said, 'Send him. He'll do just fine'," says DeLucia. "But we didn't want him to do fine, we wanted him to do great!" Austin, now in fourth grade, towers over his classmates, but he's hardly the only older kid in his grade. At Clemmons last year, 40 percent of the kindergartners started when they were 6 instead of 5. Other parents say they understand where the DeLucias are coming from but complain that red-shirting can make it hard for other kids to compete. "We're getting to the point," says Bill White, a Clemmons dad whose kids started on time, where "we're going to have boys who are shaving in elementary school."

Parents are acutely aware of the pressure on their kids, but they're also creating it. Most kids learn to read sometime before the end of first grade. But many parents (and even some teachers and school administrators) believe—mistakenly—that the earlier the kids read independently, write legibly and do arithmetic, the more success they'll have all through school.

Taking a cue from the success of the Baby Einstein line of videos and CDs, an entire industry has sprung up to help anxious parents give their kids a jump-start. Educate, Inc., the company that markets the learning-to-read workbooks and CDs called "Hooked on Phonics," just launched a new line of what it calls age-appropriate reading and writing workbooks aimed at 4-year-olds.

In the last three years, centers that offer school-tutoring services such as Sylvan Learning Centers and Kumon have opened junior divisions. Gertie Tolentino of Darien, Ill., has been bringing her first grader, Kyle, for Kumon tutoring three times a week since he was 3 years old. "It's paying off," she says. "In kindergarten, he was the only one who could read a book at age 5." Two weeks ago Tiffani Chin, executive director of Edboost, a nonprofit tutoring center in Los Angeles, saw her first 3-year-old. His parents wanted to give him a head start, says Chin. "They had heard that kindergarten was brutal" and they wanted to give him a leg up.

All this single-minded focus on achievement leaves principals like Holly Hultgren, who runs Lafayette Elementary School in Boulder County, Colo., in a quandary. In this area of Colorado, parents can shop for schools, and most try to get their kids into the top-performing ones. Two years ago Hultgren moved to Lafayette from a more affluent school, in part to help raise the tests scores, improve the school's profile and raise attendance. Every day Hultgren has to help her staff strike a balance between the requirements of the state, the expectations of parents—and the very real, highly variable needs of all kinds of 5- and 6-year-olds. She is adamant that her staff won't "teach to the test." Yet, in keeping with her district's requirements, on the day before the first day of kindergarten, students come in for a reading assessment. Sitting one-on-one with her new teacher, a little girl named Jenna wrinkles her nose and in a whispery voice identifies most of the letters in the alphabet and makes their sounds. Naming words that start with each letter is harder for her. Asked to supply a word that starts with B, Jenna scrunches her face and shakes her head.

Hultgren is ambivalent about high-stakes testing. The district reading test, administered three times a year, helps parents see how the school measures up and helps teachers see "exactly what kind of instruction is working and what isn't." But the pressure to improve scores makes it hard for teachers to stay sensitive to the important qualities in children that tests can't measure—diligence, creativity and potential—or to nurture kids who develop more slowly. "I worry," she says, that "we are creating school environments that are less friendly to kids who just aren't ready."

Some scholars and policymakers see clear downsides to all this pressure. Around third grade, Hultgren says, some of the most highly pressured learners sometimes "burn out. They began to resist. They didn't want to go along with the program anymore." In Britain, which adopted high-stakes testing about six years before the United States did, parents and school boards are trying to dial back the pressure. In Wales, standardized testing of young children has been banned. Andrew Hargreaves, an expert on international education reform and professor at Boston College, says middle-class parents there saw that "too much testing too early was sucking the soul and spirit out of their children's early school experiences."

While most American educators agree that No Child Left Behind is helping poor kids, school administrators say a bigger challenge remains: helping those same kids succeed later on. Until he resigned as Florida's school chancellor last year, Jim Warford says he scoured his budget, taking money from middle- and high-school programs in order to beef up academics in the earliest years. But then he began to notice a troubling trend: in Florida, about 70 percent of fourth graders read proficiently. By middle school, the rate of proficient readers began to drop. "We can't afford to focus on our earliest learners," says Warford, "and then ignore what happens to them later on."

What early-childhood experts know is that for children between the ages of 5 and 7, social and emotional development are every bit as important as learning the ABCs. Testing kids before third grade gives you a snapshot of what they know at that moment but is a poor predictor of how they will perform later on. Not all children learn the same way. Teachers need to vary instruction and give kids opportunities to work in small groups and one on one. Children need hands-on experiences so that they can discover things on their own. "If you push kids too hard, they get frustrated," says Dominic Gullo, a professor of early education at Queens College in New York. "Those are the kids who are likely to act out, and who teachers can perceive as having attention-span or behavior problems."

There are signs that some parents and school boards are looking for a gentler, more kid-friendly way. In Chattanooga, Tenn., more than 100 parents camped out on the sidewalk last spring in hopes of getting their kids into one of the 16 coveted spots at the Chattanooga School for Arts and Sciences (CSAS), a K-12 magnet program that champions a slowed-down approach to education. The school, which admits kids from all socioeconomic backgrounds, offers students plenty of skills and drills but also stresses a "whole-child approach." The emphasis is not on passing tests but on hands-on learning.

Two weeks ago newly minted kindergartners were spending the day learning about the color red. They wore red shirts, painted with bright red acrylic paint. During instructional time, they learned to spell RED. Every week each class meets for a seminar that encourages critical thinking. Two weeks ago the first graders had been read a book about a girl who was adopted. Then, the class discussed the pros and cons of adoption. One girl said she thought adoption was bad because "a kid isn't with her real mom and dad." A boy said it was good because the character "has a new mom and dad who love her." The children returned to their desks and drew pictures of different kinds of families. At CSAS, students are rarely held back, and in fourth grade—and in 12th grade—more than 90 percent of students passed the state's proficiency tests in reading last year.

Tiffany Aske says she wishes she could have found a school like CSAS in Oakland. Instead, they're pulling up stakes and moving to a suburban community in Washington where the school system seems more stable and has more outdoor space, and where the kids have more choices during the school day. In some ways, they feel as if they're swimming against the current. Most of their friends are scrambling, paying top dollar for houses in high-performing school districts. The Askes say they're looking for something more important than high test scores. "We want flexibility," says Tiffany. Ashlyn is a bright girl, says her mom, "but she's only a child." And childhood takes time.

with Matthew Philips, Julie Scelfo, Catharine Skipp, Nadine Joseph, Paul Tolme and Hilary Shenfeld

Comment: WOW! What does one say? How about "dog racing anyone?" I darkened the paragraph I thought most important. Having worked with preschoolers for over 25 years I have to say that the primary catch for teaching this age child is the element of fun. The word fun after this article makes the GS sound like a circus, but ANYONE will learn more if it's fun. That's why people who have hobbies often turn them into a job they love - because hobbies are fun.

Children should come to school because they love it and because it's new, different and exciting every day. Teaching children to read takes time. There's a window, and any teacher worth her pay knows when a child is ready to go through the window. Pushing a child through the window won't make reading come any quicker.

I'm a big advocate of recess because I'm a big advocate of down time. Down time for me is not TV or other mind deadening activities. Down time is time spent engaging in an activity that lets another activity "sink in."

When I went back to college, I worked from 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. at home. I had as many as 30 children in my house most of the time. I took as many as 22 credit hours a semester at night, and what I found was that small increments of learning through the day helped me master every class. I had a book open in the kitchen all the time. I wrote my senior research thesis the same way - little increments. It was a 400 page Medieval novel.

Learning is a life long task that we LEARN to do as children. Learning is active, not passive, and learning means letting things take their time to sink in. A real learner never studies for a test; he or she is always prepared to answer the hard questions any time any place.

So how do we get kids to do this? We first make school a community, a social unit of love and compassion, and then we add the education. That can't be done if school is a quicksand of quick swimmers who bob up an down gasping for time and air and presence of mind.

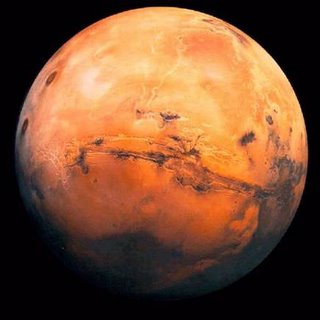

Yesterday we looked at the solar system. Most of the children understood what it was and where they lived and we actually had a discussion about Pluto. Abby said it was no longer a planet. We discussed that. These are 4 and 5 year old children. You can't get better than that.

2 comments:

Judy,

I loved David's solar system. Its already framed on my desk. I showed it to a coworker, who was amazed that a four year old could understand the concept. I can't thank you enough for everything your school has given David.

MaryBeth

I obviously love the school too and all they teach Abby. You can also imagine that I am excited that she remembered something we discussed at home too!!!

Post a Comment